The myth of stability and certainty

And where to learn the truth of what we have instead

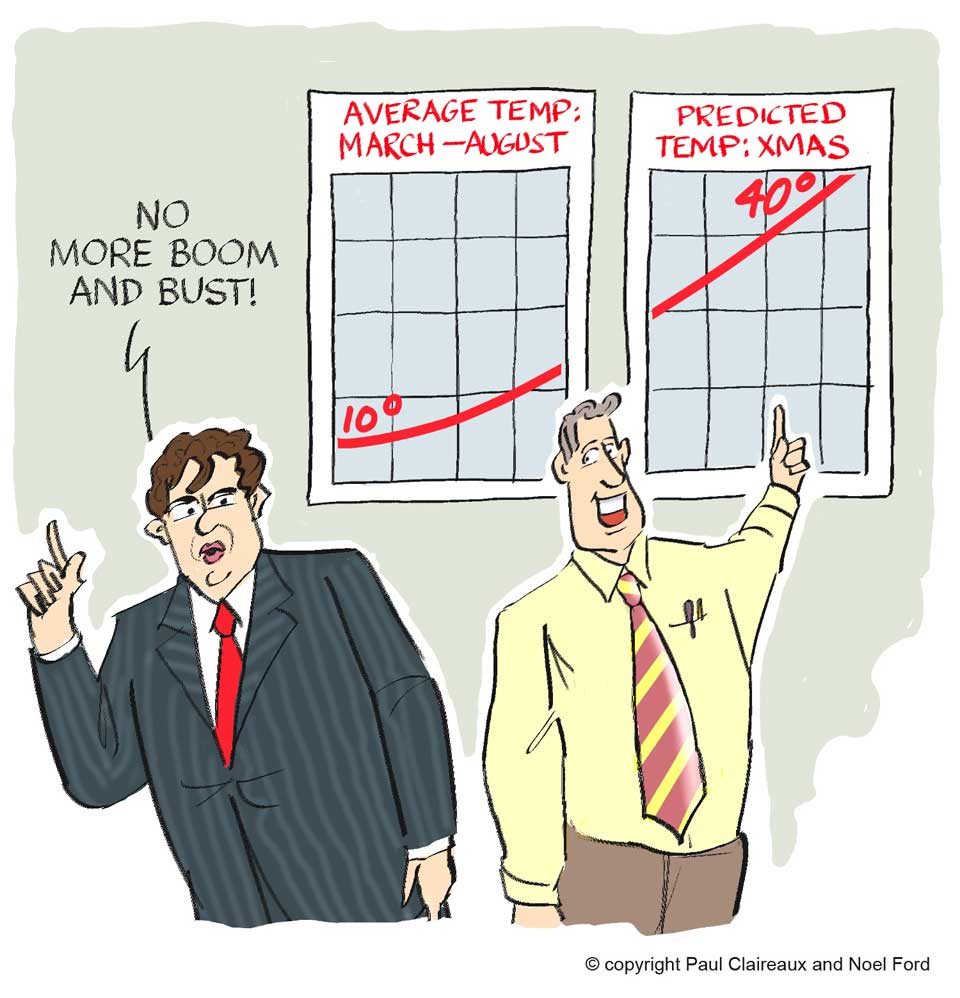

Whatever your interest (or leaning) in politics, and unless you’re very young, you surely can’t have missed Theresa May’s promise of stability and certainty in the run up to the messy 2017 UK election.

But if you did miss it (or even if you didn’t) – here’s a funny reminder

Of course, Mrs May gave up on her ‘Strong and Stable’ mantra shortly after this ridicule went viral, only to replace the word ‘stability’ with ‘certainty’ in her speech in Downing street the morning after the election.

You might wonder how she could genuinely believe in ‘certainty’ after her ‘certain’ victory in that election vanished into thin air, but there you are, that’s human nature for you.

When people ‘believe’ in something, they don’t let go of that belief easily, regardless of the evidence in front of them.

Is this another Tory bashing blog?

No, absolutely not.

I hold no candle for any political party – and I was certainly not impressed by Jeremy Corbyn either.

According to him, in a confident interview with Andrew Marr on the BBC (just after the election he lost), we could all have ‘stability’ if we’d only put him into power.

So, the important question is this…

Can any politician deliver ‘stability or certainty’?

Well of course not.

Indeed, I’m quite amazed that they even dare utter those words.

After all, it’s still only just over ten years since the last financial crisis.

And that one arrived under the stewardship of Mr Prudence and Stability himself, Gordon Brown.

Remember him?

The simple truth is that politicians of all parties just keep making this promise, and they do so because it’s what a lot of people want to hear.

The politicians (or their PR advisers) know that growth and stability is what people yearn for. And a great many voters are (or rather were, before Covid) taken in by the idea that politicians can deliver it.

But they cannot deliver this, and just saying they can, does not make it real.

Political and economic systems are inherently unstable

Economic systems are driven by our natural ‘herd-like’ animal behaviour – and by our collective mood swings (worldwide) between optimism and pessimism.

Our moods towards political parties also swing back and forth – depending on how convinced we are by the promises they make about their preferred economic school of thought.

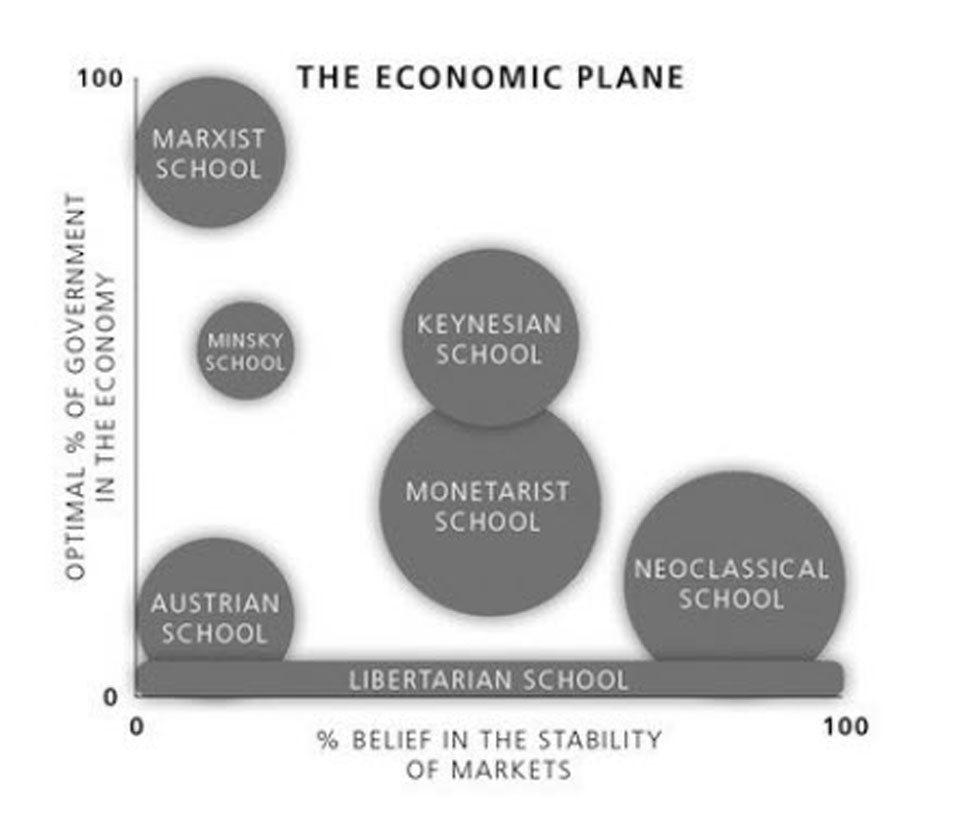

What’s interesting is how the preferred school of thought – moves around like wildebeest on the East African Serengeti.

That, by the way, is the excellent analogy from Dr George Cooper in his book, ‘Fixing Economics’ – which includes this excellent diagram to explain the plain of economic ideas.

I’ve seen a lot of useless, two-dimensional models in my time, but this one is brilliant, and if you want to understand Economics, that book is the best place to start.

Find it with some of my other favourites here.

Here’s an extract from George Cooper’s book

The very fact that there are so many disparate schools of economics both on and off our economic plane is a symptom that all is not well in the field of economics.

A further aspect of the problem is inconsistency over time. Up to this point, I have described the neoclassical school as the consensus opinion. This is true today, but it was not always the case.

We could imagine the economic plane as a real plane populated with all of the economists in the world.

Over the last century or so there would have been some considerable migrations around the plane – I have in my mind’s eye something that looks like the herds of wildebeest on the East African Serengeti.

In the 1930s through to the 60s, the bulk of the herd would have been clustered around the Keynesian school, with substantial populations in the Marxist, Austrian and neoclassical quarters.

In the 1970s, there would have been a migration away from the Marxist and towards the monetarist areas.

From the 1980s onwards, the drift would have been increasingly toward the entire herd moving into the neoclassical quadrant.

In 2008, as Lehman Brothers was failing, there would have been a stampede away from the neoclassical quarter towards the Minsky zone as everyone suddenly rejected the silly notion of an inherently stable economy and embraced Minsky’s idea of an inherently unstable economy.

It was around this time that the term “Minsky moment” became briefly fashionable.

Then in the years since 2008, Minsky has been forgotten and the herd has quickly drifted back to recolonise the neoclassical zone, conveniently forgetting that it ever left.

The remarkable Mr Minsky

You can learn more about Minsky’s ideas – and the other big Economics Schools of thought in George Cooper’s book, but in a nutshell, what Minsky realised is this.

During periods of ‘stability,’ people gain confidence and start borrowing more and spending more.

This leads to a stronger economy and more confidence and more borrowing until the borrowing gets out of hand and the system goes into reverse.

Sound familiar?

In summary, as Minsky himself said:

Okay, but what has this got to do with your money?

Well, unfortunately, some investment advisers share Theresa May and Gordon Brown’s view that somehow our economy (and the markets) can be tamed – and be made stable.

This minority group of advisers tend to accept the fact that markets ‘wobble’ a bit – from time to time – but they take the view that markets always ‘right’ themselves in relatively short timescales and carry on upwards as before.

So, their message, when the SH1T really hits the fan is always,

Wait for the ‘V’ shaped recovery,

and you’ll be fine.

You have heard that, right?

In short, their message is, ‘ignore the wobbles’ – which is great advice except for the very time when it’s wrong.

Reality is quite different

Those ‘ignore the wobbles’ ideas are absurd – and simply not born out by the evidence.

Sure, there are a lot of markets which have, historically, enjoyed long periods of growth with only minor wobbles but most developed markets have also experienced times of severe 50%+ falls from time to time.

Indeed there have been three such falls in the UK Stockmarket in the past 50 years and two of those turned up in the past 20 years.

So problems tend to cluster also, a fact noted by Benoit Mandelbrot a long time ago and beautifully explained to John Authers when he was at the FT, here.

The longer-term tidal flows of economies and markets do not stop simply because a single politician demands stability or because it feels good to believe it.

So if a politician (or your adviser) promises you stability or certainty, just ‘tune out’ and start listening to someone else.

Sign up to my newsletter, if you’ve heard enough from the ‘sell-side’ of wealth management- and want to read more balanced facts.

Thanks for dropping in

Paul

For more ideas to achieve more in your life and make more of your money, sign up to my newsletter

As a thank you, I’ll send you my ‘5 Steps for planning your Financial Freedom’ and the first chapter of my book, ‘Who misleads you about money?’

Also, for more frequent ideas – and more interaction – you can join my Facebook group here

Share your comments here

You can comment as a guest (just tick that box) or log in with your social media or DISQUS account.

Discuss this article